Do we need an affirmative action program for conservative academics?

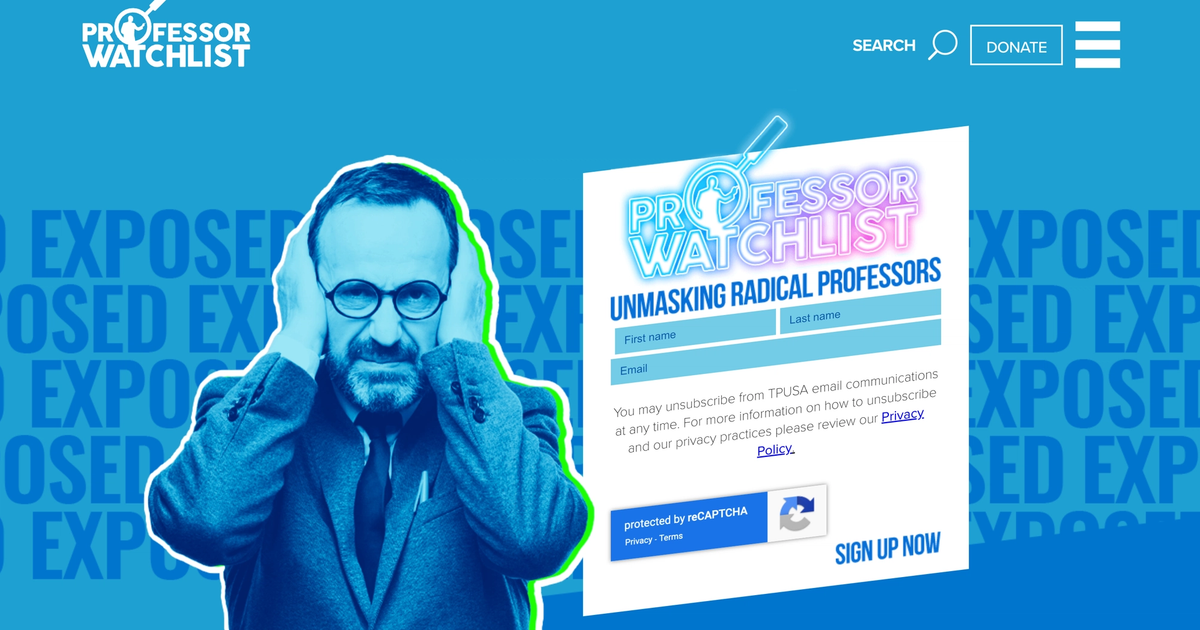

One of the most widely circulated claims from the controversial activist Charlie Kirk was that conservative students, scholars and ideas were not being given a fair hearing within American universities. To address this issue Kirk set up the website professorwatchlist.org where college students were encouraged to report their professors who ‘discriminate against conservative students, promote anti-American values and advance leftist propaganda in the classroom.’ Once reported, Kirk’s organization Turning Point USA would ‘call out’ these academics with summaries of their supposedly offensive views.

The Chronicle of Higher Education reports that in 2025 there were over 300 academics on the watchlist. Christabel K. Cheung, a cancer researcher and Associate Professor at the University of Maryland claims that after ‘she was placed’ on the website she ‘was repeatedly harassed. She said she received hundreds of threatening emails.’ Tobin Miller Shearer, a Professor of History at the University of Montana, received ‘death threats after being placed on a Turning Point USA target list‘. Albert Ponce, a Professor of Political Science at Diablo Valley College, had his family targeted after he appeared on the watchlist. ‘Hate mail turned into death threats against him and his family. Pictures of his family, including his then 9-year-old daughter, appeared online.’ Saida Grundy, a Professor of Sociology and African American and Black Diaspora Studies at Boston University was placed on this watchlist and others, after which she ‘received countless death threats and demands that the university fire her. In her first year on the faculty, her office was broken into and vandalized, she said.’ Though it is hard to do, given this doxxing and harassment of fellow academics, let us step back from this violence for a second, and ask: what does the data on conservatives in academia tell us? Relatedly, is the answer to hire more conservative academics – not to placate the violent online mob, but to address more legitimate concerns from reasonable conservative voices?

A 2015 review of the existing literature on the political affiliations of American academics concluded that ‘58–66 per cent of social science professors in the United States identify as liberals, while only 5–8 per cent identify as conservatives’. Surveys of Humanities disciplines ‘find that 52–77 per cent of humanities professors identify as liberals, while only 4–8 per cent identify as conservatives … In the United States as a whole, the ratio of liberals to conservatives is roughly 1 to 2’. This is re-enforced by a study that surveyed academics at forty high-ranked American universities on their political affiliations, which was published in 2018 in Academic Questions (the journal of the National Association of Scholars, a politically conservative education advocacy organization). This research found that faculty in Economics supported the Democrats over the Republicans to a ratio of 5.5/1, in Political Science the Democrat support was 8.2/1, in History 17.4/1, in English 48.3/1 and the study found no registered Republicans at the universities surveyed in Anthropology, Communications, Gender Studies, Africana Studies, and Peace Studies. The Harvard Crimson reported that a 2023 survey found that: ‘Of the nearly four hundred Harvard faculty members who responded … only three per cent of the ones declaring their politics identified as conservative.’

Why are there so few conservative academics in Humanities and Social Sciences departments? As the data shows, the highest ratios of conservatives are in Business Schools and this reflects where conservatives are most likely to work outside of academia, namely in corporations or in private businesses. Up until WWII, there were proportionately a lot more conservatives in Arts Faculties, but after the war conservatives were not generally drawn to studying for PhDs and becoming academics as conservatives became more economically oriented and post war, conservatism became more anti-intellectual, as noted by liberal scholars like Richard Hofstadter and also conservatives like Roger Scruton.

In response to data like that presented above and the claims of Charlie Kirk, conservative activist Christopher Rufo has called for the complete overhaul and even defunding of American universities. Such views have been highly influential on the Trump administration. One example of the effect of these ideas is the pressure being brought to bear on Harvard to have greater ‘viewpoint diversity’ amongst its faculty, as outlined in the widely reported upon letter ‘mistakenly’ sent to Harvard University by the Trump administration on 11 April, 2025. The letter demanded that Harvard must:

‘commission an external party [approved by the federal government]…to audit the student body, faculty, staff, and leadership for viewpoint diversity, such that each department, field, or teaching unit must be individually viewpoint diverse…Every department or field found to lack viewpoint diversity must be reformed by hiring a critical mass of new faculty within that department or field who will provide viewpoint diversity; every teaching unit found to lack viewpoint diversity must be reformed by admitting a critical mass of students who will provide viewpoint diversity.’

Many academics would argue that the claims made in this letter to Harvard are bad faith arguments that have been made for highly instrumental reasons, such as profoundly weakening the role of universities in American political debate. I agree with this interpretation, but it is nonetheless important to argue explicitly against the letter sent to Harvard and other similar actions, not least because university administrators in the current political environment are likely to feel like they want to ‘do something’ to placate governments and interest groups arguing for greater ‘viewpoint diversity.’ Increasing the number of conservative academics employed by university departments is not necessarily going to lead to a better understanding of society or even a better understanding of a greater range of political ideas and interests.

In a letter that also calls for ‘merit-based hiring reform,’ as opposed to any application of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) principles, the letter to Harvard is contradictory in its advocacy of an affirmative action program set up to employ more conservative scholars. Such hypocrisy is not hard to find in the current Trump administration, in an interview in March 2025 J. D. Vance said: ‘Are we willing to defend people even if you disagree with what they say? If you’re not willing to do that I don’t think you’re fit to lead Europe or the United States of America.’ When he posted this interview on X, Vance added that: ‘Shutting down free speech will destroy our civilization.’ After the assassination of Charlie Kirk, Vice President Vance was at the head of efforts to shut down criticisms of Kirk’s political views.

Turning back to the Trump administration’s letter to Harvard we see identity diversity and viewpoint diversity being treated as the same thing. To be fair, many people do this, but this is a category error and leads to unhelpful essentialising. Identity diversity refers to the range of ethnicity, race, gender, or political orientations of staff and students within universities and academic departments, whereas viewpoint diversity refers to the range of ideas taught to students. I run units where white men teach Judith Butler and Asian women teach the cultural conservative Christopher Lasch; this commitment to intellectual pluralism is far more common in the best university departments than activists like the late Charlie Kirk tend to claim.

Interrogating the political views and voting records of scholars before they are appointed to university departments is not the answer to having a more pluralistic curricula; instead, a better goal is to have a diverse range of materials well taught to students. Few would claim that academics need to be fascists to teach the history and ideology of fascism effectively. I am currently completing a book on conservative ideas in the study of International Relations and from my research the evidence is that scholars who are ideologically committed to conservatism have not been particularly effective at outlining conservative ideas. Overwhelmingly, the scholarship that has emerged from self-described conservatives is overly partisan and too partial. A good example is Henry Nau’s book Conservative Internationalism (2015) which in many ways is a celebration of the approach to foreign policy supposedly adopted by President Ronald Reagan, who Nau was an adviser to before he became a professor at George Washington University. Nau contends that Reagan was ‘the quintessential conservative internationalist’ a claim that is not particularly convincing if we use the word ‘internationalist’ in its commonly understood manner. The overwhelming weight of evidence suggests that Reagan was far more an American nationalist than an internationalist. Nau’s book has been widely celebrated by conservative scholars and the ideas in it have been influential on other conservative academics, making it the most important work written by a conservative International Relations academic on US foreign policy. However, it offers no great insight into conservatism as it fails to present even Reagan’s conservatism in its full variety.

The aim of all academics should be to avoid the type of hagiography that Nau’s work falls into. Instead, sensible viewpoint diversity requires skilled academics knowledgeable enough to teach and inquire into a variety of viewpoints with healthy scepticism about one theory having all the answers. An introductory class or textbook on twentieth century ideologies without a discussion of communism would be missing an important element; I similarly believe that an introductory International Relations class or textbook without a section on conservative theory is missing a highly influential worldview. Universities do not necessarily need to employ a diverse range of advocates to teach a diverse range of theories. Rather, understanding the most important and influential viewpoints and theories should be well within the skillset of any academic employed in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The ability to teach a variety of viewpoints is one sign of academic excellence and should be a key responsibility that academics have towards students – particularly in introductory classes.

The idea that academics need to be identified with a viewpoint when they are being hired and then stick with that viewpoint throughout their career is at once disastrous and implausible. How could scholars be prevented from changing their minds about theories when they acquire new knowledge or when circumstances in the world change? Moreover, the idea that students should undergo the same ideological tests, as suggested in the letter to Harvard, is stultifying and lamentable. Classifying academics and students by ideology would weaken the fundamental academic qualities of open-mindedness and boundless curiosity.

The key criteria for employment as an academic has hopefully been, and should remain, depth of knowledge and the quality of one’s research and teaching. The idea that universities should have teachers and researchers to represent or reflect the views of the general public is to confuse their role with parliaments. Universities should be striving to research and teach a broad range of ideas deeply, and this is best done by highly credentialed scholars – not by podcasters, ex-politicians, and activists. By all means, invite a broad range of people to universities to give guest lectures and to talk with academics and students. However, in an age of celebrity and hot takes, we do not need ideological appointments parachuted into universities. Instead, we need universities to back the ability of their academic specialists to study societies broadly and deeply in order to present humanity in its full richness.